This summer 2018 I went to Russian Arctic to work on Long-tailed ducks. When I tell some people I went to the Russian Arctic, I often receive two comments that are misconceptions about this place. So here, I will try to debunked those myths, and tell you what the Arctic is and what it is not, in my own view, of course.

One common response I get from people is: “Waow, it was probably cold.”

Well, yes and no.

Sure, when we arrived, it was cold, I was happy to have a warm shapka with me. I wore big ski gloves most days, just so my fingers would be functioning when extracting the birds from the nets. But then, I have poor blood circulation in general, and can comfortably wear a sweater when everyone else around is in t-shirt. Oh, and there was this day when we had to stop working as my co-worker could not hold a pencil anymore.

Picture: Thiemo Karwinkel

Picture: Thiemo Karwinkel

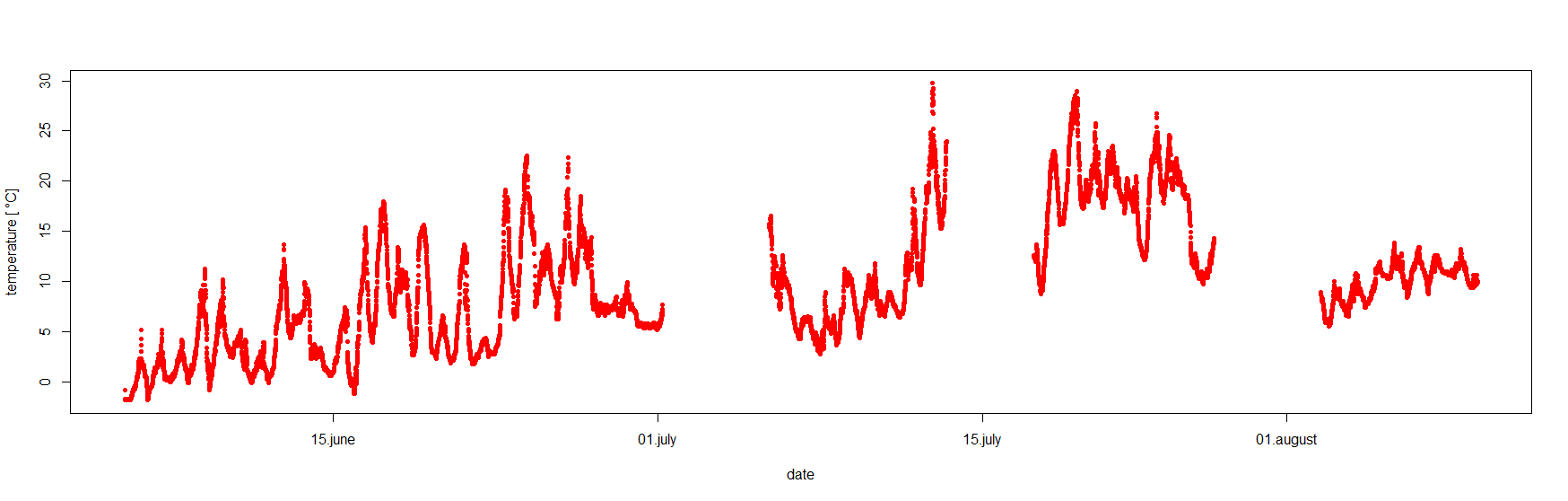

Eventually good weather arrived, and it was hot, sweating hot. Here is a graph of the outside temperature (from a place protected from direct sun light). The landscape around camp was sand dunes and we were joking that we were in the Sahara and not Siberia! Which brings me to the second debunked myth.

Click on the graph to enlarge.

“Oh, so you were in Siberia.”

Well, no.

Russian Arctic and Siberia are not necessarily the same. Siberia is this vast part of Russia that it East of the Ural mountain, it covers 77% of whole of Russia (see map below). I was West of the Ural mountain, so technically, I was not in Siberia. I was in a region called Yamal-Nenets Autonomous District.

The little red dot is where I was. Siberia is to the East.

So, now that you know that it can be warm in the Arctic and that Russia Arctic can be, but is not always Siberia, you might want to hear about long-tailed ducks, the reason I was there in the first place.

Long-tailed ducks are in serious decline, the population wintering in the Baltic Sea saw a 65% decline since the 1990s. The species is now globally threatened and classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN since 2012. We have yet to understand the reason for this decline. By monitoring the reproductive success, monitoring the food availability on the breeding grounds, and following individual’s movements outside of the breeding season, we will get a better picture of what is happening to those ducks of the north. Stay tuned for more info on the ducks and my new life in Germany.